Arizona Hikes, Travels & Tours

Pictures, Photos, Images, & Reviews.

Squaw Creek Pueblo, Ruin

Ancient Hohokam Ruins.

Agua Fria National Monument, Arizona.

George and Eve DeLange

Google Map To Squaw Creek Pueblo, Ruin. Agua Fria National Monument, Arizona.

View Larger Map

Click On Any Of The Following Links By Amazon.Com

For Books, & Videos About About Arizona Native American Ruins. No Obligation!

|

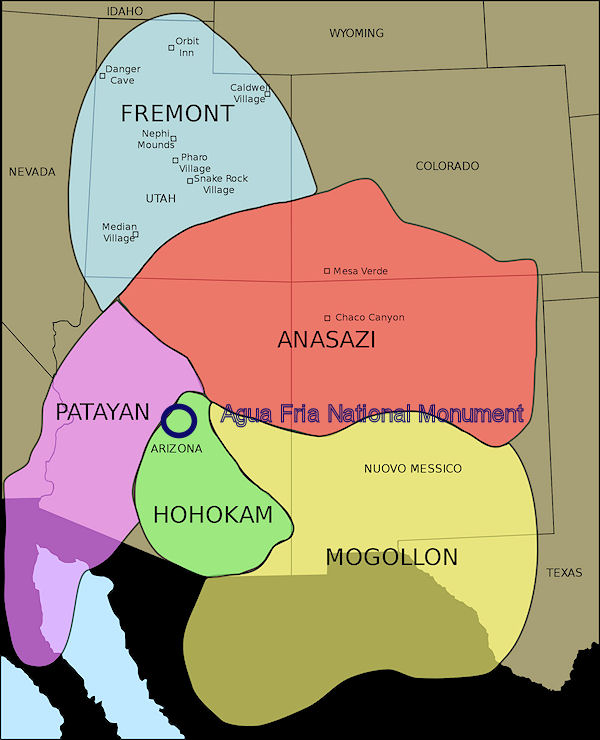

| Map Of Ancient Southwestern Civilizations In The United States. Circled Area Is Approximate Location Of Agua Fria National Monument, Arizona. A Brief Discussion Of These Ancient Civilizations Is Below. Note: All Civilization Locations Are Approximate & Some Overlap. No-One Knows The Exact Boundaries! There Probably Was Some Overlaping At Agua Fria National Monument. |

|---|

| Squaw Creek Pueblo, Ruin. Ancient Hohokam Ruins. Photo April 19, 2011. |

|---|

The Squaw Creek Pueblo Ruin contains an estimated 150 + rooms and is probably the largest pueblo site of the over 450 pueblo's in the Agua Fria National Monument. There is a smaller satellite Pueblo a few hundred feet northwest of the main pueblo. There are many petroglyphs nearby. Some are even painted with a redish color. A long and high defensive wall surrounds the pueblo on all three sides that are not protected by a natural cliff. This ruins is also named, "Las Mujeres" or "The Women." This ruins is un-restored. This is typical of what an un - restored ruins looks like. Notice the wall details and you can see the stones that were used to level the main rocks of the wall. Just imigine how an ancient man had placed the small stone in place as he was building the walls of Pueblo la Plata! A Google Earth Map search marks the northwest side of the "Squaw Creek Pueblo Ruin" at 34o 07' 59.7" N 112o 00' 23.69" W. The elevation is about 3,998 feet. As to; who were the people who lived at Squaw Creek Pueblo? No one seems yet to know. All we seem to agree on, is that their historic record ends abruptly in the mid 15th century. One picture being painted of its former inhabitants is controversial, but it paints a picture of many epic battles, alliances, treaties, and military expeditions among the stone fortresses strewn across the highlands of the Perry Mesa area. It comes to us from a study conducted during the 1990's by Museum of Northern Arizona; Senior Research Anthropologist Dr. David Wilcox; Tonto National Forest archaeologist J. Scott Wood; and Gerald Robertson Jr., an amateur archeologist from the Verde Valley. They concluded that the Perry Mesa people were "organized for war." They speculated that the Perry Mesa civilization was part of the "Verde Confederacy", an alliance that also consisted of people from the Tonto Basin and Flagstaff area. They speculated that the Perry Mesa pueblos created a defensive wall against the great Hohokam civilization inhabiting the Salt River Valley and the Gila River areas to the south. Other archeologists disagree with that theory stating that the petroglyphs of Perry Mesa show a more peaceful people. We doubt that the argument will be settled any time soon. But, we think that sides would agree that preserving this ancient area is of great importance to us all. Considering the location of the Agua Fria National Monument, Perry Mesa, and the "Pueblo la Plata Ruin"; we should expect to see some characteristics of at least one of the various southwestern ancient cultures at the "Pueblo la Plata Ruin".

To Get To Squaw Creek Pueblo Ruin:

You will soon cross a cattle guard and Bloody Basin Road becomes well graded dirt road before reaching an Agua Fria National Monument Kiosk (here you can stop and pick up a map). Then drive about 11.3 miles. Turn right onto a rough road which is suitable only for high clearance vehicles. Then drive the road for about 2.8 mile. Then turn left onto another rough road which is suitable only for high clearance vehicles. Then drive the road for about 1.6 mile. Then turn right onto another rough road which is suitable only for high clearance vehicles. Then drive the road for about 2.4 mile. You will be at the northwest side of the Squaw Creek Pueblo Ruin. Note: Do Not Drive A Low Clearance Vehicle On these roads. It Won't Make It!

|

| Squaw Creek Pueblo, Ruin. | Squaw Creek Pueblo, Ruin. |

|---|

If you are planning to visit the "Squaw Creek Pueblo, Ruin". And if you are coming from outside of Arizona, you could fly into the Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport and then rent a car. We recommend renting a high clearence vehicle. There are many hotels and motels in the area. We have some links to Priceline.com on this page since they can arrange all of your air flights, hotels and car. We also have some links to Altrec.com on this page since they are a good online source for any outdoor camping gear and clothing that you may need. We of course, appreciate your use of the advertising on our pages, since it helps us to keep our pages active.

|

THE MAJOR ANCIENT SOUTHWESTERN PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES:

The Anasazi (ah-nah-SAH-zee):

The Anasazi were referred to as "Hisatsinom" by their Hopi descendants. The Navajo name, Anasazi, is said to mean "ancient enemies." Other, Native Americans simply refer to these ancient people as the "old ones." It is thought that the early Anasazi people lived in small groups of a few families, with perhaps 10-25 people living in each village, on an average, for about 10 - 20 years. Then, as the Anasazi population exploded during the last half of the 11th century, and, as their society grew, the Anasazi villages banded together in order to control their water supply with various earthen dams and irrigation systems, therefor, making them able to develop other crops with deep roots, giving the Anasazi greater access to food crops. With more plentiful food, they developed aboveground storage facilities. They began to build grand houses into the stones of canyons and canyon walls. They began to use their former underground dwellings as "spiritual centers", called "kivas." The kiva's, became meeting places for the tribes and clans and they were used for the religious teaching and rituals that the Anasazi practiced. The kiva's usually contained a hole in their center, which is said to have symbolized the "sipapa," or the place of origin through which the Anasazi ancestors first emerged into this world. Even today to the descendents of these people, the kiva has remained a sacred site, a place of spiritual energy and space. The Anasazi also developed elaborate trading routes, enabling them to travel to far away places, trading for goods which they needed. These trade routes also allowed other people from other regions to come into the Anasazi villages to trade. Some of the better known Anasazi settlements are: Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde, New Mexico. We don't really know for sure what caused the collapse of such a thriving civilization but by A.D. 1,130-1,150 A.D. many of the Anasazi towns were deserted. A group of the Anasazi called "The Western Anasazi" are known to our anthropologists today as, the "Sinagua".

The Fremont Culture:

The Fremont Culture inhabited sites in what is now Utah, parts of Nevada, Idaho, and Colorado from 700 to 1,300 AD. It was located north of, contemporaneous to, but distinctly different from, the Anasazi Culture. The Fremont people built villages of from about 10 to 100 pithouses It is thought that not all of the pithouses would have been in use at once since pithouses are not permanent residences. They are usually discarded after about ten years and build another. What today look like large villages might have only been a few families living in the same place over several decades. Those villages that were near stream beds had agricultural fields that were irrigated with excavated ditches. Nearby were often groups of two or three pithouses which may have been field houses or stopping points for those hunter-gatherers who were away from home. The Fremont people often built rectangular, free-standing, above-ground structures out of adobe brick called granaries for the use of the community. Some granaries were built in the middle of villages for communal use; while others were placed in hard-to-reach places, such as in caves, rockshelters, or on canyon walls. Archaeologists believe that storing grain in these hard to reach locations, accessed by ladders or rock-climbing, are evidence that there was strong competition for the stored grain. The Fremont people produced a type of pottery that was primarily a gray-pasted pottery, sometimes painted with elaborate geometric designs. They produced baskets and worked leather, they also made polished stone balls and human figurines made of fired clay. They also made distinctive small triangular notched and projectile points for use as arrow tips. Like other ancient people, they also made metate slabs and grinding stones The reason for the disappearance of the Fremont culture is unknown. One consideration was the drought associated with the "Medieval Little Ice Age" (1,300-1,800 AD). We know the climate in the Great Basin became significantly colder and drier. Severely impacting the feasibility of farming during that time.

The Sinagua (seen-ah-gwa):

After volcanic activity improved soil conditions around 1,000 AD, the Sinagua began to thrive by assimilating various elements from the major cultural groups. From the Hohokam they acquired village life and the use of ball courts; from the Anasazi they adopted cliff dwellings and water conservation practices; from the Mogollon they adopted pottery styles. By the late 1,450s, the same natural and social stresses that destroyed the other cultures of the region engulfed the Sinagua as well. By about 1,425, they had completely disappeared. But, their dwellings and religious shrines can be found all over Central Arizona. One is even located in a city park in the city of Phoenix! The early Sinagua sites consist of pit houses. Their later structures more closely resembled the pueblo architecture found in other cultures throughout the southwestern United States. The name Sinagua was given to this culture by archaeologist Harold Colton, founder of the Museum of Northern Arizona. Sinagua is derived from the Spanish words "sin" meaning "without" and "agua" meaning "water", referring to the name "Sierra Sin Agua" which was originally given by the Spanish explorers to the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff, Arizona. Colton also distinguished between two different Sinagua cultures. The Northern Sinagua were clustered around the Flagstaff area, with Elden Pueblo, Walnut Canyon National Monument, Wupatki National Monument, being the best-known publicly-accessible sites. The Southern Sinagua were found throughout the Verde Valley of Central Arizona. Most notable sites open to the public being; Montezuma's Castle, Montezuma's Well, Tuzigoot National Monument, the Palatki Archaeological Site, and the V-Bar-V Petroglyph Site. The last known recording of Sinagua occupations for any of the Sinagua sites are of those in Montezuma Castle National Monument in about 1,425 AD. The reasons for the abandonment of their habitation sites are not yet known; but warfare, drought, and clashes with the newly-arrived Yavapai people are possible suggestions. Several of the Hopi clans trace their roots to immigrants from the Sinagua culture. The Hopi clans believe their ancestors left the Verde Valley for religious reasons.

The Hohokam (ho-ho-KAHM):

The Hohokam culture, which spanned some 1450 years � from 1 A. D. in the first millennium to A. D. 1450 � suddenly appeared and vanished into the darkness of history. During that time, the Hohokam raised new standards in innovation, art, and craftsmanship. They also had trade and cultural connections into Mesoamerica. Based upon the first archaeological evidence, researchers believed that early Hohokam pioneers into northern Sonora and southern Arizona, imported a more advanced Mesoamerican influence into the area, founding the Hohokam culture, around the beginning of the first millennium. Based upon later archaeological evidence, other researchers believed that local descendants of the ancient hunting and gathering traditions of the desert, responded to influences from Mesoamerica and emerged as the Hohokam. Yet other students have suggested that the Hohokam immigrants arrived from an unknown Mesoamerican region and swept across the deserts of southern Arizona and northern Mexico. It is thought by those researchers that the Hohokam immigrants probably over ran the hunter/gatherers in the region of southern Arizona, sometime in the second half of the first millennium. Yet other investigators say that the Hohokam region was nothing more than a Mesoamerican frontier outpost. And others believe that the Hohokam culture represented nothing more than a local cultural development with a Mesoamerican tint. In any case, not much is known about their origins. The Hohokam occupied a geologically and ecologically diverse region, which extended from the basin and range and the low desert country of northern Sonora and southern Arizona northward into the Mogollon Rim escarpment and onto the southwestern edge of the Colorado Plateau. The Hohokam people had many settlements in the Gila and Salt River valleys of southern Arizona. They built rectangular pit houses from earth, rather than stone, and lived in small villages. They cremated their dead and placed the ashes in a specially prepared pit Although the Hohokam relied a great deal on hunting and gathering, they also were skilled farmers and excellent engineers. They were a peaceful people who cooperated to build large canal networks. Some of their canals were over ten miles long and used gravity to control water flow and to flush out the silt. Between the 7th and 14th centuries they built and maintained these extensive irrigation networks along the lower Salt and middle Gila rivers that rivaled the complexity of those used in the ancient Near East, Egypt, and China. These were constructed using relatively simple excavation tools, without the benefit of advanced engineering technologies. These highly successful agricultural techniques produced a surplus of food. Villages and populations grew. Over the next 1500 years the Hohokam expanded their settlements into the Tucson Basin, then to the Phoenix area, and as far north as present-day Flagstaff.

The Patayan Culture (puh-TIE-yuhn):

The word "Patayan" comes from the Yuman language and means the "old people." The archaeological record of the Patayan Culture is very poorly understood. The Patayan Culture was first described in 1945 by the archaeologist Malcolm Rogers when he published a definition and chronology of the Patayan Culture. His survey records identified hundreds of desert sites located in the harsh dry conditions of the southwestern deserts. These harsh desert conditions have limited the amount of ongoing archaeological fieldwork in the areas so there are not many Patayan Culture remains to be found. The Patayan people were highly mobile and did not build large structures or accumulate numerous possessions. We think that many Patayan sites may have been destroyed by floods in the various river valleys where some of them may have raised crops. We do find a significant number of the Patayan cultures archaeological remains appearing in about 875 A.D. We also find many of their cultural characteristics that even continued into historic times. It is beleived that the Patayan Culture may have originally emerged along the Colorado River, extending from the area around modern day Kingman northeast to the Grand Canyon. The Patayan people appear to have practiced floodplain agriculture, a theory based upon the descovery of manos and metates used to process corn in these areas. Stone points and other tools for hunting and hide preparation have been found in their areas, suggesting that their economy was based upon both agriculture, and hunting & gathering. Excavation of their early sites contain several shallow pithouses or surface "long houses," consisting of a series of rooms arranged in a linear manor. These dwellings usually had a pitroom at the east end, perhaps for storage or ceremonial activities. Dwellings built later on were much less well defined and show loose groupings of their varying dwelling types. The Patayan people made both baskets and pottery. Their ceramics were not adopted until about 700 AD. Patayan pottery is usually plain ware, visually resembling the 'Alma Plain' of the Mogollon people. But, the Patayan pottery was made using the paddle-and-anvil method, and thier pottery is more reminiscent of Hohokam pottery. This use of paddle-and-anvil construction; suggests that either people from the Hohokam or influenced by the Hohokam first settled into the territory of the Patayan. The Lowland Patayan pottery is made of fine buff colored riverine clays, while the upland Patayan pottery is made of a more coarse and a deeper brown colored riverine clay. The Patayan pottery painted ware, is made sometimes by using red slips, and appear to be heavily influenced by the styles and designs of the neighboring southwestern cultures.

The Mogollon (Mug-ee-yo-n):

The name Mogollon comes to us by way of Emil Haury, who named it after the Mogollon Mountains of New Mexico, which had been named after Don Juan Ignacio Flores Mogoll�n, the Spanish Governor of New Mexico from 1712-1715 AD. The Mogollon culture appears to have arisen from the earlier Cochise culture. The Mogollon people settled high-altitude desert areas in what is today; New Mexico, Sonora, Chihuahua, and western Texas. It is thought that the Mogollon were, initially, foragers who augmented their subsistence efforts by farming. Then it is beleived that after about 1,000 years, their dependence upon farming probably increased. The earliest Mogollon villages were little more than several pit-houses excavated into the ground surface, with stick and thatch roofs supported by a network of posts and beams, and faced on the exterior surfaces with earth. Mogollon village sizes increased through time and by the 11th century they had surface pueblos made of rock and earth walls, and with roofs supported by post and beam networks. Anthropologists believe that, sometime between 900 and 1,100 AD, the Anasazi culture absorbed much of the Mogollon culture, merging the traits from both. However, Mogollon cliff dwellings are found to be more common during the 13th and 14th centuries. Total abandonment of these areas, however, did not occur until about 1,450 AD. It is believed that this merged culture contributed to the various cultural backgrounds of the Hopi, Zuni and Acoma people. The best-known remains of the Mogollon are their pottery. This art was developed over a period of nearly a thousand years. As it became more diverse, simple geometric designs on brown were replaced by more complex red-on-white and finally by the well-known black-on-white designs of the famous Mimbres pottery. After their early innovations, the Mogollon culture evolved very little and was gradually swallowed up by the more dynamic cultures from the north. Thus, by about 1,450 AD they had merged physically and culturally with the Anasazi. The various prehistoric Pueblo cultures, which included the Anasazi, developed in the northern areas of what is now Arizona and spread south, reaching the Salt and Gila Rivers by about 1,200 AD. By 1,400 - 1.450 AD, these cultures were breaking up and soon disappeared. By the time the Spaniards arrived in the sixteenth century, the local native americans had no recollection of the people who had built the magnificent Casa Grande structures or the cliff dwellings in the southwest.

|

We Are Proud Of Our SafeSurf Rating!

Click On Any Of The Following Links By Amazon.Com

For Books, & Videos About About Arizona Native American Ruins. No Obligation!

Click On Any Of The Following Links By Amazon.Com

For Books, & Videos About Touring Arizona. No Obligation!