Trinity Atomic Bomb Site.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Hikes, Travels, & Tours

Pictures, Photos, Images, & Reviews.

October 1, 2011

October 1, 2011

Google Map To Trinity Atomic Bomb Site.

Ground Zero! Exactly Where It Exploded!

Long Structure In Image, Covers Original Ground!

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

View Larger Map

Click On Any Of The Following Links By Amazon.Com

For Books Or Videos About The Atomic Bomb. No Obligation!

Trinity Atomic Bomb Explosion. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Conducted By The United States Army On July 16, 1945. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Trinity Atomic Bomb Site. Ground Zero! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Photo Taken October 1, 2011.

While The Soil Is Redish In Color, Look Carefully And You Can See A Slight Green Tinge To The Soil.

It Is The Radioactive Fusion Glass Mineral, Trinitite, Formed By The Atomic Bomb Blast & Heat!

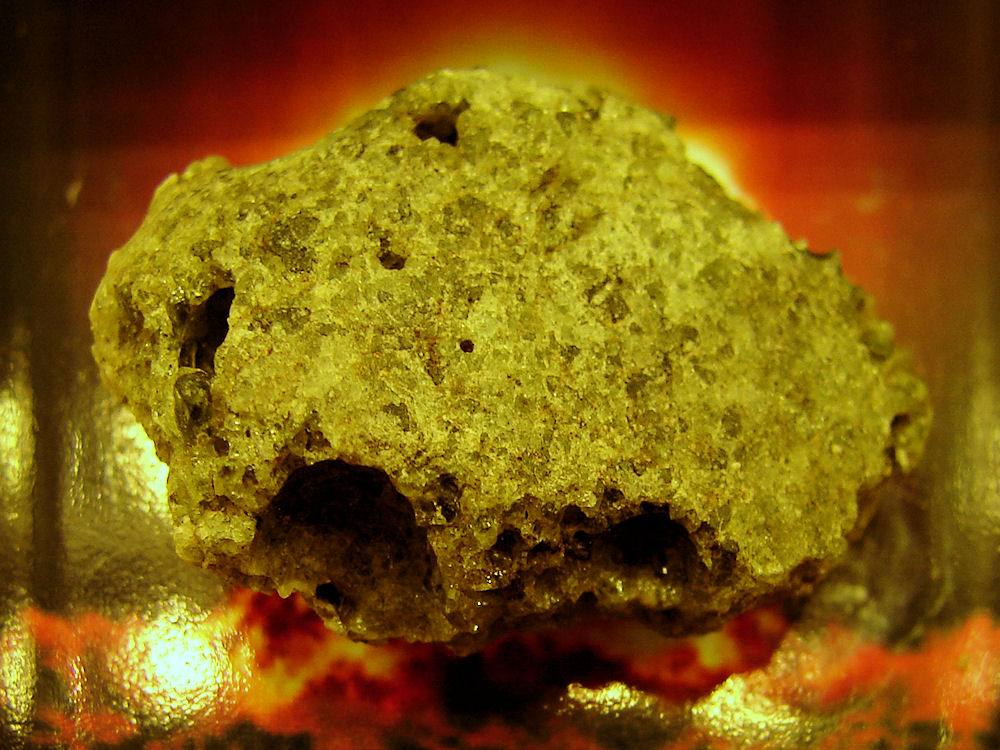

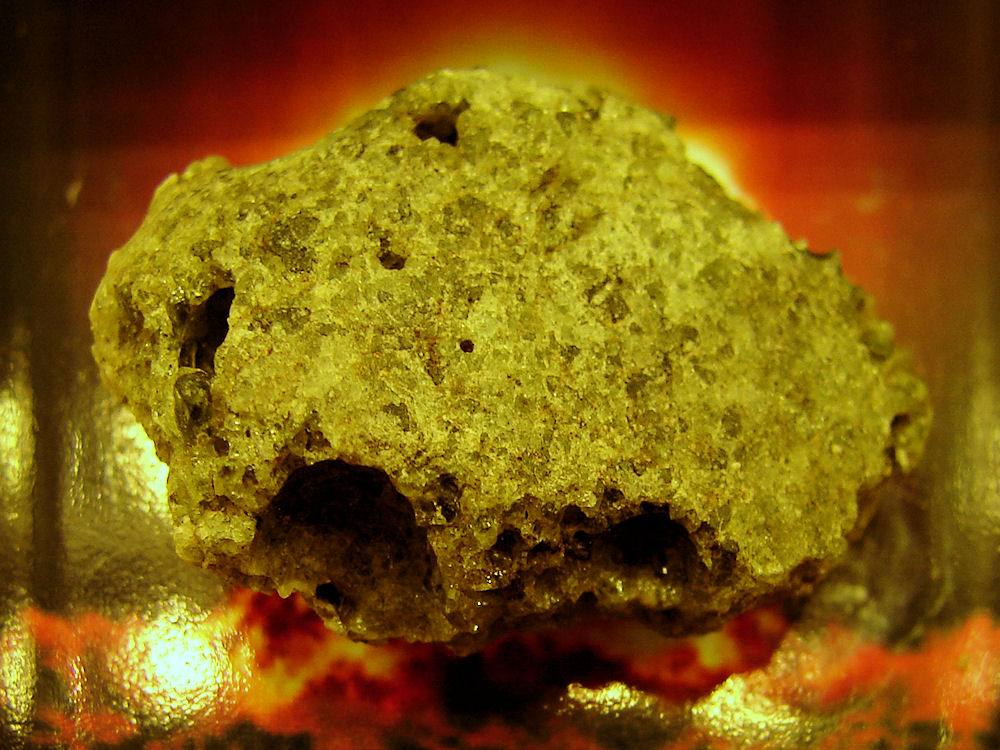

Trinitite Formed At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Site. Ground Zero! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Formed By The Atomic Bomb Blast & Heat!

Today The Radiation From This Sample Is Less Than 1 Micro Roentgen / Hour.

Remains Of The 214 - Ton Steel Canister. Code - Named "Jumbo"

At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Site. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

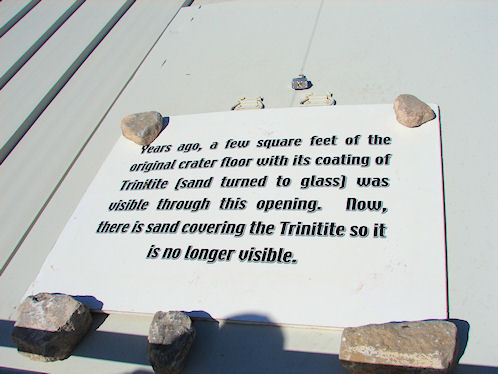

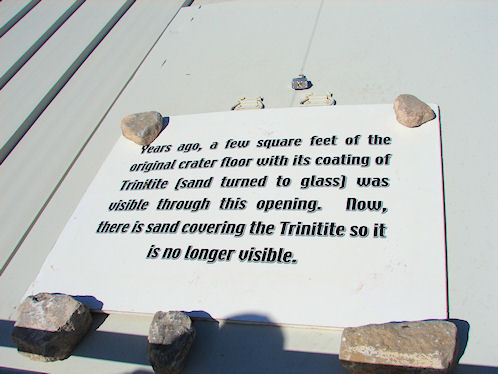

This Low Metal Shed Covers A Small Area Of The Site To Protect An Intact Section.

At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Site. Ground Zero! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

We wish to thank Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia for some of the images and information on this page. We share information with Wikipedia.

Prior to the Trinity Project; the Los Alamos Laboratory was organized in 1943 to design a nuclear weapon that the Army hoped would win World War II.

Over the course of the next two years, the Los Alamos Laboratory designed a weapon using uranium-235 assembled by firing one part of a critical mass into another, but this technique was found to be inadequate for plutonium, because isotopic impurities of plutonium-240 would cause it to predetonate.

During the second year of its existence, the Los Alamos Laboratory was reorganized to solve the much more difficult problems of implosion - the uniform compression of plutonium to a super- critical mass � that had been proposed by Seth Neddermeyer of the California Institute of Technology, John von Neumann of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton and several others.

Because of the many uncertainties attending almost every phase of the implosion weapon, it was decided that an implosion bomb would have to be tested.

Various test sites were considered, and a location in the Jornado del Muerto desert in central New Mexico was finially selected.

Harvard physicist Kenneth Bainbridge planned it's construction and University of Minnesota physicist John Williams supervised the construction of the facilities.

Los Alamos Laboratory Director J. Robert Oppenheimer, named the site "Trinity" after a poem by John Donne that he had been reading.

To capture any of the plutonium that might be lost if the new type of bomb fizzled, Manhattan Engineer District Commander Leslie Groves ordered a container, called "Jumbo," to be built at a cost of more than $12 million.

Jumbo was the largest item that had ever been shipped by rail, and several trestles on the railroads from the factory that built it in Ohio to the Trinity site had to be rebuilt.

By the time Jumbo arrived, the production of plutonium at the Hanford Engineer Works had increased so that Leslie Groves, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and several of his colleagues believed that there was less chance of a failure.

Therefore, Jumbo was set aside and hung not far from Ground Zero, to serve as an indicator of the power of the bomb. It emerged unscathed although the tower was completely destroyed.

Trinity site's construction was finished during the winter and spring of 1945, and by June, Bainbridge was ready to calibrate the instruments that would be used to measure the blast, heat and radiation of the "Gadget" by using a 100-ton stack of high explosives tagged with fission products from the Hanford pile. The 100-ton test made it possible for the Los Alamos scientists to refine their instruments before the much larger blast to come from the gadget.

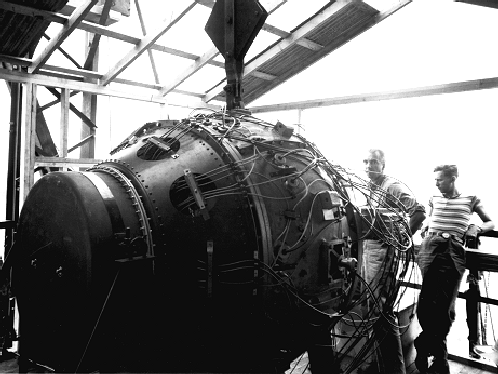

The design of the gadget had been fixed in February 1945 when Groves ordered a design freeze so that the device could be ready by July. A conservative solid-core design by Robert Christy, a member of the Theoretical Physics (T) Division, the gadget required the development of detonators, fuses and high-explosive lenses that were not yet perfected. Given a clear goal, however, Los Alamos scientists and technicians succeeded in producing all of the components of the device successfully by July 13.

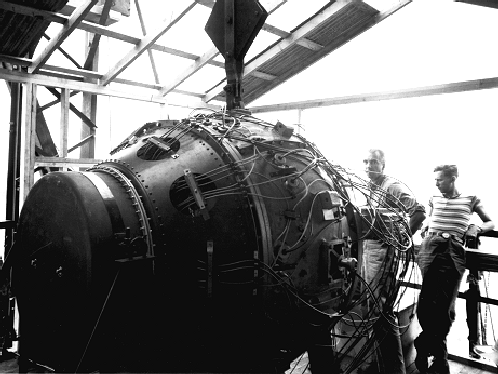

On that day, assembly of the gadget began at Trinity. A crew led by Norris Bradbury, a professor of physics at Stanford University who had come to Los Alamos by way of the Naval Reserve and Dahlgren Proving Grounds, assembled the high-explosive lenses that had been brought from V-site at Los Alamos the day before escorted by Harvard professor George Kistiakowsky, who had led the high-explosives effort at the Laboratory since November 1943. Bradbury, Kistiakowsky and five �G (gadget) engineers' began their work at 1 p.m. After the tamper and the active material were inserted into the spherical case, the final high-explosives were inserted, "as slowly as the G-engineers wished," said Kistiakowsky.

On Saturday, July 14, 1945, the assembled gadget was hoisted to the top of the 100-foot tower on which it would be detonated. The firing unit was wired by late afternoon. Bradbury's schedule for Sunday, July 15, called for the staff to "look for rabbit's feet and four-leaved clovers." The detonation was scheduled for 4 a.m., Monday, July 16.

Meantime, Los Alamos scientists had conducted a test of the implosion assembly at Los Alamos that seemed to indicate that it might not work.

As the test approached, the weather worsened and a thunderstorm broke over the site late on July 15, and the test was postponed from 4 a.m. to 5:30 a.m. to avoid the possibility of a rain-out of fission products from the bomb cloud.

In some of the nearby settlements of New Mexico, members of the health physics team were ready to evacuate the population should the test exceed it's expected yields.

As predicted, the weather cleared and the countdown for the test was begun at 5:10 a.m. "As we approached the final minute," Leslie Groves recalled, "the quiet grew more intense. At the control point, Joe McKibben, who had been with Project Y since the beginning, threw the main switch that started the precise automatic timer at minus 45 seconds. Only one person, Donald Hornig, a physical chemist from Harvard University, on the arming party, could stop the explosion.

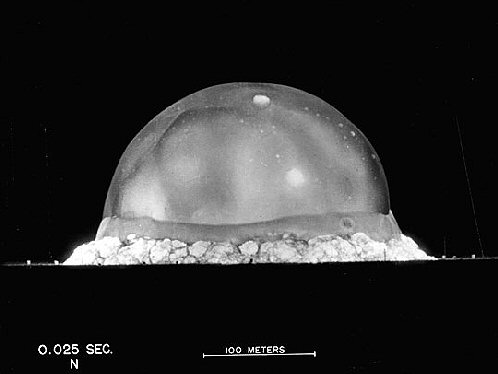

At 5:29:45 a.m., the Trinity Gadget exploded with a force of about 21,000 tons of TNT, evaporating the tower on which it stood. Leslie Groves' deputy, Gen. Thomas Farrell, wrote that the "whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun. It was golden, purple, violet, gray and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. Seconds after the explosion came first the air blast pressing hard against the people, to be followed almost immediately by the strong, sustained awesome roar that warned of doomsday and made us feel we puny things were blasphemous to dare tamper with the forces heretofore reserved for the Almighty." Oppenheimer was reminded of the quotation from his favorite Sanskrit text, the Bhagavad-Gita, "I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds." To his brother, Frank, who had helped construct the site, he said only, "It worked."

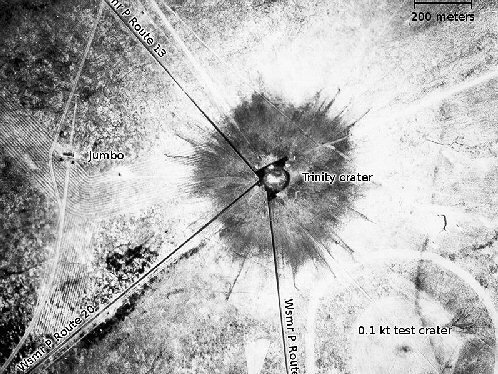

Immediately after the test a Sherman M-4 tank, equipped with its own air supply, and lined with two inches of lead went out to explore the site. The lead lining added 12 tons to the tank's weight, but was necessary to protect its occupants from the radiation levels at ground zero. The tank's passengers found that the 100-foot steel tower had virtually disappeared, with only the metal and concrete stumps of its four legs remaining. Surrounding ground zero was a crater almost 2,400 feet across and about ten feet deep in places. Desert sand around the tower had been fused by the intense heat of the blast into a jade colored glass. This atomic glass was given the name Atomsite, but the name was later changed to Trinitite.

Due to the intense secrecy surrounding the test, no accurate information of what happened was released to the public until after the second atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan. However, many people in New Mexico were well aware that something extraordinary had happened the morning of July 16, 1945. The blinding flash of light, followed by the shock wave had made a vivid impression on people who lived within a radius of 160 miles of ground zero. Windows were shattered 120 miles away in Silver City, and residents of Albuquerque saw the bright light of the explosion on the southern horizon and felt the tremor of the shock waves moments later.

The true story of the Trinity test first became known to the public on August 6, 1945. This is when the world's second nuclear bomb, nicknamed Little Boy, exploded 1,850 feet over Hiroshima, Japan, destroying a large portion of the city and killing an estimated 70,000 to 130,000 of its inhabitants. Three days later on August 9, a third atomic bomb devastated the city of Nagasaki and killed approximately 45,000 more Japanese. The Nagasaki weapon was a plutonium bomb, similar to the Trinity device, and it was nicknamed Fat Man. On Tuesday August 14, at 7 p.m. Eastern War Time, President Truman made a brief formal announcement that Japan had finally surrendered and World War II was over after almost six years and 60 million deaths!

On Sunday, September 9, 1945, Trinity Site was opened to the press for the first time. This was mainly to dispel rumors of lingering high radiation levels there, as well as in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Led by General Groves and Oppenheimer, this widely publicized visit made Trinity front page news all over the country.

Trinity Site was later encircled with more than a mile of chain link fencing and posted with signs warning of radioactivity. In the early 1950s most of the remaining Trinitite in the crater was bulldozed into a underground concrete bunker near Trinity. Also at this time the crater was back filled with new soil. In 1963 the Trinitite was removed from the bunker, packed into 55-gallon drums, and loaded into trucks belonging to the Atomic Energy Commission (the successor of the Manhattan Project). Trinity site remained off-limits to military and civilian personnel of the range and closed to the public for many years, despite attempts immediately after the war to turn Trinity into a national monument.

In 1953 about 700 people attended the first Trinity Site open house sponsored by the Alamogordo Chamber of Commerce and the Missile Range. Two years later, a small group from Tularosa, NM visited the site on the 10th anniversary of the explosion to conduct a religious service and pray for peace.

Regular visits have been made annually in recent years on the first Saturday in October instead of the anniversary date of July 16, to avoid the desert heat. Later Trinity Site was opened one additional day on the first Saturday in April. The Site remains closed to the public except for these two days, because it lies within the impact areas for missiles fired into the northern part of the Range.

In 1965, Range officials erected a modest monument at Ground Zero. Built of black lava rock, this monument serves as a permanent marker for the site and as a reminder of the momentous event that occurred there. On the monument is a plain metal plaque with this simple inscription: "Trinity Site Where the World's First Nuclear Device Was Exploded on July 16, 1945."

During the annual tour in 1975, a second plaque was added below the first by The National Park Service, designating Trinity Site a National Historic Landmark. This plaque reads, "This site possesses national significance in commemorating the history of the U.S.A."

Los Alamos had succeeded in producing a nuclear weapon only two years, three months and 16 days after it was formally opened. The implosion bomb was, however, a vast departure from the nuclear weapon first envisaged. That device, the gun-type uranium weapon, did not need to be tested. Farrell commented to Groves immediately after the Trinity test, "The war is over." "Yes," Groves replied, "just as soon as we drop one or two of these things on Japan."

Norris Bradbury, later became the director of Los Alamos Laboratory for several decades, upon J. Robert Oppenheimer's departure.

The author of this page, George DeLange, had a grandfather named John Oliver Hawkins; who knew President Harry S. Truman. Evidentally they were both residents in Harrisonville, Missouri at the same time during their lives.

George recalls his grandfather telling him, how President Truman told his grandfather, some time after the Atomic Bomb explosion had been made public; that the pictures he had seen, "scared the hell out of me!"

THIS SITE IS ONLY OPEN TO THE PUBLIC, TWO DAYS OF THE YEAR: 1ST SATURDAY OF APRIL & 1ST SATURDAY OF OCTOBER!

How To Get There:

(1) Stallion Gate Entrance - Exit I-25 on mile marker 139 (San Antonio, N.M.) and head 12 miles east or exit Highway 54 onto Highway 380 and head west 53 miles of Carrizozo, N.M. Turn on the Stallion Gate entrance and head south five miles of Highway 380.The gate is opened from 8:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. Visitors are allowed to enter and exit unescorted anytime during these special days.

(2) Alamogordo Alternative - The Alamogordo Chamber of Commerce sponsors a convoy for visitors that desire a tour. The Alamogordo caravan meeting site will be at the Tularosa High School Athletic Field Parking lot. Turn west off Hwy. 54/70 in Tularosa at Higuero St. Proceed west to La Luz Ave. Turn right on La Luz Ave. (north) to athletic field. Line up will begin at 7 a.m. Caravan departs at 8 a.m. Visitors entering this way will travel as an escorted group to and from Trinity Site. The drive is 145 miles roundtrip and there are no service station facilities on the missile range. The convoy is scheduled to leave Trinity Site at 12:30 or 1 p.m., depending on its size, for the return to Tularosa. The convoy may leave later if there is a large number of vehicles returning.

Cameras are allowed at Trinity Site but their use is strictly prohibited anywhere else on White Sands Missile Range.

For more information contact the missile range Public Affairs Office at (575) 678-1134.

For more information about the construction of the first atomic bomb, we suggest going to our pages about the McDonald Ranch, the Bradbury Museum, And Los Alamos Historical Museum in Los Alamos.

If you are planning to visit . And if you are coming from outside of New Mexico, you could fly into Albuquerque International Sunport and then rent a car.

Albuquerque International Sunport (IATA: ABQ, ICAO: KABQ, FAA LID: ABQ) is a public airport located 3 miles (5 km) southeast of the central business district of Albuquerque, a city in Bernalillo County, New Mexico, United States. It is the largest commercial airport in the state

We actually found it easier to stay in nearby Socorro, New Mexico at the Holiday Inn Express.

There are many hotels and motels in New Mexico and Colorado, and if you need a place to stay; Priceline.com can arrange that for you.

We have personally, booked flights, hotels, and vacations; through Priceline.com and we can highly recommend them. Their website is also easy to use!

We have some links to Priceline.com on this page since they can arrange all of your air flights, hotels and car.

We of course, appreciate your use of the advertising on our pages, since it helps us to keep our pages active.

Whenever you make a purchase from a link on our page we get credit for that transaction. Again, Thanks!

Trinity Atomic Bomb Explosion.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Conducted By The United States Army On July 16, 1945.

Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Trinity Atomic Bomb Site.

Obelisk National Historic Landmark.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

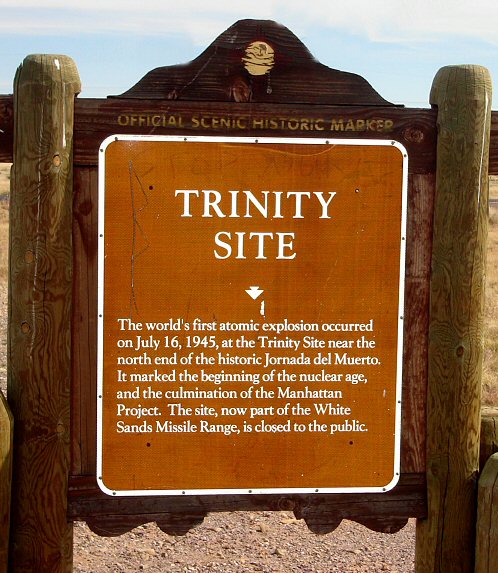

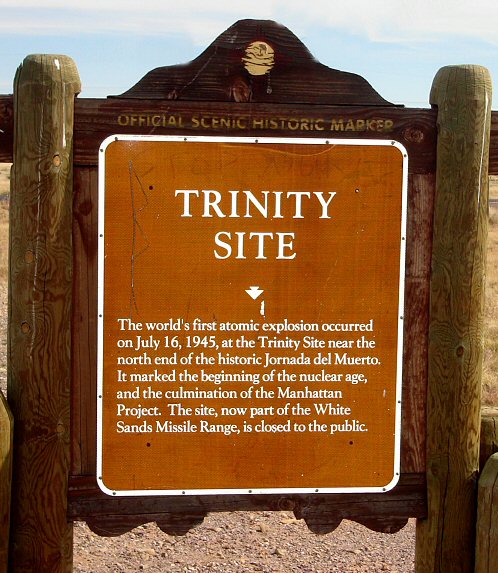

Trinity Site Historical Marker Highway Sign.

Trinity Atomic Bomb Explosion.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Trinity Atomic Bomb Site Trinity Tower.

Site Of Real Test Of Trinity Gadget. July 16, 1945.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Trinity Gadget. The Real Bomb. Fired On July 16, 1945.

Norris Bradbury On Left. Boyce McDaniel On Right.

Trinity Atomic Bomb Site.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Materials For First 100 Ton Test. May 7, 1945.

Trinity Atomic Bomb Site.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

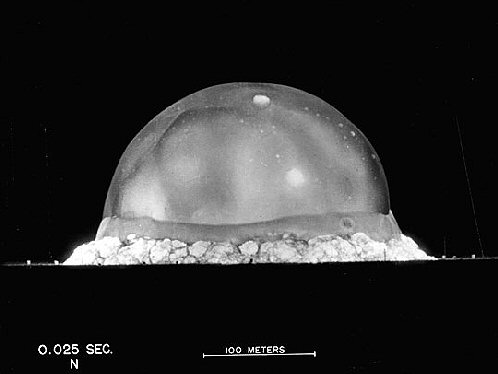

Trinity Atomic Bomb Explosion.

July 16, 1945 5:29:45 a.m. (Mountain War Time)

Photo 025 Seconds Later.

Trinity Atomic Bomb Site.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

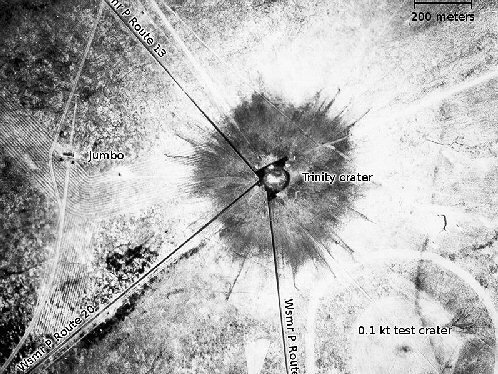

Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Trinity Crater. Trinity Atomic Bomb Site.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Trinity Atomic Bomb Site.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Trinity Atomic Bomb Site.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

Directional Signs At Tourist Drop Off Area

At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site!

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Directional Signs At Tourist Drop Off Area

At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site!

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site!

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site!

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Trinity Ground Zero Low Metal Shed

At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site!

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Door Of Trinity Ground Zero Low Metal Shed

At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site!

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

"Fat Boy" Atomic Bomb Casing.

At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site!

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Location The Trinity Atomic Bomb Site!

In Far Distance, Center Of Photo.

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Trinitite Display.

At The Trinity Atomic Bomb Site!

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Sign At The Trinity Atomic Bomb Site!

White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico.

Click On Any Of The Following Links By Amazon.Com

For Books Or Videos About The Atomic Bomb. No Obligation!

We Are Proud Of Our SafeSurf Rating!

Send E-Mail to: George DeLange: [email protected]

|

| Trinity Atomic Bomb Explosion. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Conducted By The United States Army On July 16, 1945. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. |

|---|

|

| Trinity Atomic Bomb Site. Ground Zero! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Photo Taken October 1, 2011. While The Soil Is Redish In Color, Look Carefully And You Can See A Slight Green Tinge To The Soil. It Is The Radioactive Fusion Glass Mineral, Trinitite, Formed By The Atomic Bomb Blast & Heat! |

|---|

|

| Trinitite Formed At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Site. Ground Zero! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Formed By The Atomic Bomb Blast & Heat! Today The Radiation From This Sample Is Less Than 1 Micro Roentgen / Hour. |

|

| Remains Of The 214 - Ton Steel Canister. Code - Named "Jumbo" At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Site. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. |

|

| This Low Metal Shed Covers A Small Area Of The Site To Protect An Intact Section. At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Site. Ground Zero! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. |

We wish to thank Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia for some of the images and information on this page. We share information with Wikipedia. Prior to the Trinity Project; the Los Alamos Laboratory was organized in 1943 to design a nuclear weapon that the Army hoped would win World War II. Over the course of the next two years, the Los Alamos Laboratory designed a weapon using uranium-235 assembled by firing one part of a critical mass into another, but this technique was found to be inadequate for plutonium, because isotopic impurities of plutonium-240 would cause it to predetonate. During the second year of its existence, the Los Alamos Laboratory was reorganized to solve the much more difficult problems of implosion - the uniform compression of plutonium to a super- critical mass � that had been proposed by Seth Neddermeyer of the California Institute of Technology, John von Neumann of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton and several others. Because of the many uncertainties attending almost every phase of the implosion weapon, it was decided that an implosion bomb would have to be tested. Various test sites were considered, and a location in the Jornado del Muerto desert in central New Mexico was finially selected. Harvard physicist Kenneth Bainbridge planned it's construction and University of Minnesota physicist John Williams supervised the construction of the facilities. Los Alamos Laboratory Director J. Robert Oppenheimer, named the site "Trinity" after a poem by John Donne that he had been reading. To capture any of the plutonium that might be lost if the new type of bomb fizzled, Manhattan Engineer District Commander Leslie Groves ordered a container, called "Jumbo," to be built at a cost of more than $12 million. Jumbo was the largest item that had ever been shipped by rail, and several trestles on the railroads from the factory that built it in Ohio to the Trinity site had to be rebuilt. By the time Jumbo arrived, the production of plutonium at the Hanford Engineer Works had increased so that Leslie Groves, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and several of his colleagues believed that there was less chance of a failure. Therefore, Jumbo was set aside and hung not far from Ground Zero, to serve as an indicator of the power of the bomb. It emerged unscathed although the tower was completely destroyed. Trinity site's construction was finished during the winter and spring of 1945, and by June, Bainbridge was ready to calibrate the instruments that would be used to measure the blast, heat and radiation of the "Gadget" by using a 100-ton stack of high explosives tagged with fission products from the Hanford pile. The 100-ton test made it possible for the Los Alamos scientists to refine their instruments before the much larger blast to come from the gadget. The design of the gadget had been fixed in February 1945 when Groves ordered a design freeze so that the device could be ready by July. A conservative solid-core design by Robert Christy, a member of the Theoretical Physics (T) Division, the gadget required the development of detonators, fuses and high-explosive lenses that were not yet perfected. Given a clear goal, however, Los Alamos scientists and technicians succeeded in producing all of the components of the device successfully by July 13. On that day, assembly of the gadget began at Trinity. A crew led by Norris Bradbury, a professor of physics at Stanford University who had come to Los Alamos by way of the Naval Reserve and Dahlgren Proving Grounds, assembled the high-explosive lenses that had been brought from V-site at Los Alamos the day before escorted by Harvard professor George Kistiakowsky, who had led the high-explosives effort at the Laboratory since November 1943. Bradbury, Kistiakowsky and five �G (gadget) engineers' began their work at 1 p.m. After the tamper and the active material were inserted into the spherical case, the final high-explosives were inserted, "as slowly as the G-engineers wished," said Kistiakowsky. On Saturday, July 14, 1945, the assembled gadget was hoisted to the top of the 100-foot tower on which it would be detonated. The firing unit was wired by late afternoon. Bradbury's schedule for Sunday, July 15, called for the staff to "look for rabbit's feet and four-leaved clovers." The detonation was scheduled for 4 a.m., Monday, July 16. Meantime, Los Alamos scientists had conducted a test of the implosion assembly at Los Alamos that seemed to indicate that it might not work. As the test approached, the weather worsened and a thunderstorm broke over the site late on July 15, and the test was postponed from 4 a.m. to 5:30 a.m. to avoid the possibility of a rain-out of fission products from the bomb cloud. In some of the nearby settlements of New Mexico, members of the health physics team were ready to evacuate the population should the test exceed it's expected yields. As predicted, the weather cleared and the countdown for the test was begun at 5:10 a.m. "As we approached the final minute," Leslie Groves recalled, "the quiet grew more intense. At the control point, Joe McKibben, who had been with Project Y since the beginning, threw the main switch that started the precise automatic timer at minus 45 seconds. Only one person, Donald Hornig, a physical chemist from Harvard University, on the arming party, could stop the explosion. At 5:29:45 a.m., the Trinity Gadget exploded with a force of about 21,000 tons of TNT, evaporating the tower on which it stood. Leslie Groves' deputy, Gen. Thomas Farrell, wrote that the "whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun. It was golden, purple, violet, gray and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. Seconds after the explosion came first the air blast pressing hard against the people, to be followed almost immediately by the strong, sustained awesome roar that warned of doomsday and made us feel we puny things were blasphemous to dare tamper with the forces heretofore reserved for the Almighty." Oppenheimer was reminded of the quotation from his favorite Sanskrit text, the Bhagavad-Gita, "I am become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds." To his brother, Frank, who had helped construct the site, he said only, "It worked." Immediately after the test a Sherman M-4 tank, equipped with its own air supply, and lined with two inches of lead went out to explore the site. The lead lining added 12 tons to the tank's weight, but was necessary to protect its occupants from the radiation levels at ground zero. The tank's passengers found that the 100-foot steel tower had virtually disappeared, with only the metal and concrete stumps of its four legs remaining. Surrounding ground zero was a crater almost 2,400 feet across and about ten feet deep in places. Desert sand around the tower had been fused by the intense heat of the blast into a jade colored glass. This atomic glass was given the name Atomsite, but the name was later changed to Trinitite. Due to the intense secrecy surrounding the test, no accurate information of what happened was released to the public until after the second atomic bomb had been dropped on Japan. However, many people in New Mexico were well aware that something extraordinary had happened the morning of July 16, 1945. The blinding flash of light, followed by the shock wave had made a vivid impression on people who lived within a radius of 160 miles of ground zero. Windows were shattered 120 miles away in Silver City, and residents of Albuquerque saw the bright light of the explosion on the southern horizon and felt the tremor of the shock waves moments later. The true story of the Trinity test first became known to the public on August 6, 1945. This is when the world's second nuclear bomb, nicknamed Little Boy, exploded 1,850 feet over Hiroshima, Japan, destroying a large portion of the city and killing an estimated 70,000 to 130,000 of its inhabitants. Three days later on August 9, a third atomic bomb devastated the city of Nagasaki and killed approximately 45,000 more Japanese. The Nagasaki weapon was a plutonium bomb, similar to the Trinity device, and it was nicknamed Fat Man. On Tuesday August 14, at 7 p.m. Eastern War Time, President Truman made a brief formal announcement that Japan had finally surrendered and World War II was over after almost six years and 60 million deaths! On Sunday, September 9, 1945, Trinity Site was opened to the press for the first time. This was mainly to dispel rumors of lingering high radiation levels there, as well as in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Led by General Groves and Oppenheimer, this widely publicized visit made Trinity front page news all over the country. Trinity Site was later encircled with more than a mile of chain link fencing and posted with signs warning of radioactivity. In the early 1950s most of the remaining Trinitite in the crater was bulldozed into a underground concrete bunker near Trinity. Also at this time the crater was back filled with new soil. In 1963 the Trinitite was removed from the bunker, packed into 55-gallon drums, and loaded into trucks belonging to the Atomic Energy Commission (the successor of the Manhattan Project). Trinity site remained off-limits to military and civilian personnel of the range and closed to the public for many years, despite attempts immediately after the war to turn Trinity into a national monument. In 1953 about 700 people attended the first Trinity Site open house sponsored by the Alamogordo Chamber of Commerce and the Missile Range. Two years later, a small group from Tularosa, NM visited the site on the 10th anniversary of the explosion to conduct a religious service and pray for peace. Regular visits have been made annually in recent years on the first Saturday in October instead of the anniversary date of July 16, to avoid the desert heat. Later Trinity Site was opened one additional day on the first Saturday in April. The Site remains closed to the public except for these two days, because it lies within the impact areas for missiles fired into the northern part of the Range. In 1965, Range officials erected a modest monument at Ground Zero. Built of black lava rock, this monument serves as a permanent marker for the site and as a reminder of the momentous event that occurred there. On the monument is a plain metal plaque with this simple inscription: "Trinity Site Where the World's First Nuclear Device Was Exploded on July 16, 1945." During the annual tour in 1975, a second plaque was added below the first by The National Park Service, designating Trinity Site a National Historic Landmark. This plaque reads, "This site possesses national significance in commemorating the history of the U.S.A." Los Alamos had succeeded in producing a nuclear weapon only two years, three months and 16 days after it was formally opened. The implosion bomb was, however, a vast departure from the nuclear weapon first envisaged. That device, the gun-type uranium weapon, did not need to be tested. Farrell commented to Groves immediately after the Trinity test, "The war is over." "Yes," Groves replied, "just as soon as we drop one or two of these things on Japan." Norris Bradbury, later became the director of Los Alamos Laboratory for several decades, upon J. Robert Oppenheimer's departure. The author of this page, George DeLange, had a grandfather named John Oliver Hawkins; who knew President Harry S. Truman. Evidentally they were both residents in Harrisonville, Missouri at the same time during their lives. George recalls his grandfather telling him, how President Truman told his grandfather, some time after the Atomic Bomb explosion had been made public; that the pictures he had seen, "scared the hell out of me!" THIS SITE IS ONLY OPEN TO THE PUBLIC, TWO DAYS OF THE YEAR: 1ST SATURDAY OF APRIL & 1ST SATURDAY OF OCTOBER! How To Get There: (1) Stallion Gate Entrance - Exit I-25 on mile marker 139 (San Antonio, N.M.) and head 12 miles east or exit Highway 54 onto Highway 380 and head west 53 miles of Carrizozo, N.M. Turn on the Stallion Gate entrance and head south five miles of Highway 380.The gate is opened from 8:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. Visitors are allowed to enter and exit unescorted anytime during these special days. (2) Alamogordo Alternative - The Alamogordo Chamber of Commerce sponsors a convoy for visitors that desire a tour. The Alamogordo caravan meeting site will be at the Tularosa High School Athletic Field Parking lot. Turn west off Hwy. 54/70 in Tularosa at Higuero St. Proceed west to La Luz Ave. Turn right on La Luz Ave. (north) to athletic field. Line up will begin at 7 a.m. Caravan departs at 8 a.m. Visitors entering this way will travel as an escorted group to and from Trinity Site. The drive is 145 miles roundtrip and there are no service station facilities on the missile range. The convoy is scheduled to leave Trinity Site at 12:30 or 1 p.m., depending on its size, for the return to Tularosa. The convoy may leave later if there is a large number of vehicles returning. Cameras are allowed at Trinity Site but their use is strictly prohibited anywhere else on White Sands Missile Range. For more information contact the missile range Public Affairs Office at (575) 678-1134.

For more information about the construction of the first atomic bomb, we suggest going to our pages about the McDonald Ranch, the Bradbury Museum, And Los Alamos Historical Museum in Los Alamos.

|

If you are planning to visit . And if you are coming from outside of New Mexico, you could fly into Albuquerque International Sunport and then rent a car. Albuquerque International Sunport (IATA: ABQ, ICAO: KABQ, FAA LID: ABQ) is a public airport located 3 miles (5 km) southeast of the central business district of Albuquerque, a city in Bernalillo County, New Mexico, United States. It is the largest commercial airport in the state We actually found it easier to stay in nearby Socorro, New Mexico at the Holiday Inn Express. There are many hotels and motels in New Mexico and Colorado, and if you need a place to stay; Priceline.com can arrange that for you. We have personally, booked flights, hotels, and vacations; through Priceline.com and we can highly recommend them. Their website is also easy to use! We have some links to Priceline.com on this page since they can arrange all of your air flights, hotels and car. We of course, appreciate your use of the advertising on our pages, since it helps us to keep our pages active. Whenever you make a purchase from a link on our page we get credit for that transaction. Again, Thanks!

|

|  |

| Trinity Atomic Bomb Explosion. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Conducted By The United States Army On July 16, 1945. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. | Trinity Atomic Bomb Site. Obelisk National Historic Landmark. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. |

|---|---|

|  |

| Trinity Site Historical Marker Highway Sign. Trinity Atomic Bomb Explosion. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. | Trinity Atomic Bomb Site Trinity Tower. Site Of Real Test Of Trinity Gadget. July 16, 1945. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. |

|  |

| Trinity Gadget. The Real Bomb. Fired On July 16, 1945. Norris Bradbury On Left. Boyce McDaniel On Right. Trinity Atomic Bomb Site. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. | Materials For First 100 Ton Test. May 7, 1945. Trinity Atomic Bomb Site. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. |

|  |

| Trinity Atomic Bomb Explosion. July 16, 1945 5:29:45 a.m. (Mountain War Time) Photo 025 Seconds Later. Trinity Atomic Bomb Site. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. | Trinity Crater. Trinity Atomic Bomb Site. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. |

|  |

| Trinity Atomic Bomb Site. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. | Trinity Atomic Bomb Site. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. Courtesy: Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. |

|  |

| Directional Signs At Tourist Drop Off Area At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. | Directional Signs At Tourist Drop Off Area At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. |

|  |

| At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. | At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. |

|  |

| Trinity Ground Zero Low Metal Shed At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. | Door Of Trinity Ground Zero Low Metal Shed At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. |

|  |

| "Fat Boy" Atomic Bomb Casing. At TheTrinity Atomic Bomb Ground Zero Site! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. | Location The Trinity Atomic Bomb Site! In Far Distance, Center Of Photo. White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. |

|  |

| Trinitite Display. At The Trinity Atomic Bomb Site! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. | Sign At The Trinity Atomic Bomb Site! White Sands Missile Range. New Mexico. |

Click On Any Of The Following Links By Amazon.Com

For Books Or Videos About The Atomic Bomb. No Obligation!

We Are Proud Of Our SafeSurf Rating!